The last time I saw Matt Beedle was a dozen years ago at his wedding. I was a newlywed myself and Kate was pregnant with Luke at the time. My third year of seminary was about to start and, as such, Matt and Amy figured I had been trained up enough to preach the homily. If I recall, the Gospel that day was the story of the transfiguration on the mountaintop – a fitting theme for our relationship.

The last time I saw Matt Beedle was a dozen years ago at his wedding. I was a newlywed myself and Kate was pregnant with Luke at the time. My third year of seminary was about to start and, as such, Matt and Amy figured I had been trained up enough to preach the homily. If I recall, the Gospel that day was the story of the transfiguration on the mountaintop – a fitting theme for our relationship.

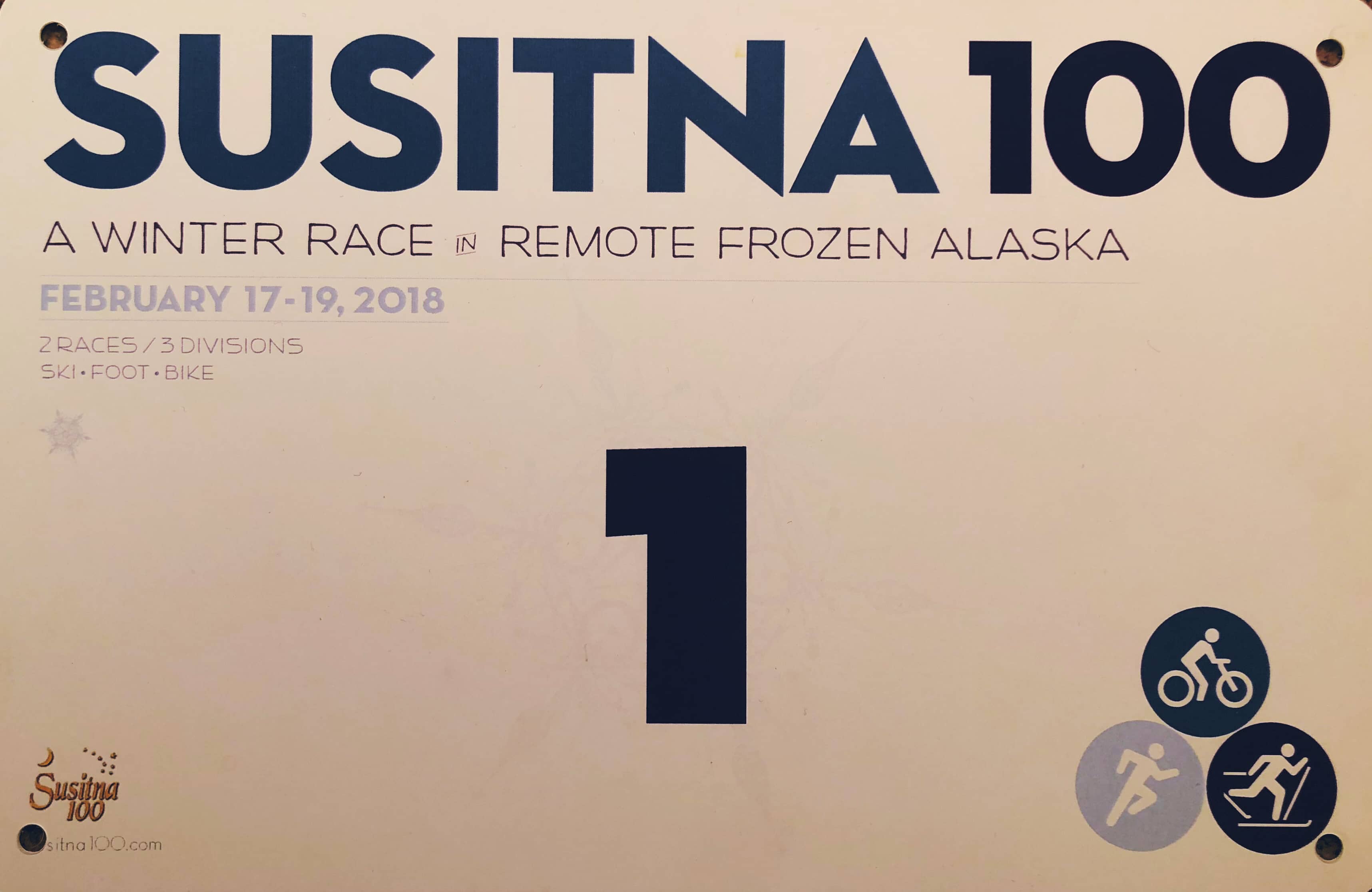

Matt and I grew up in Juneau, Alaska climbing mountains together. Thunder, Juneau, McGinnis, Jumbo, Roberts, Nugget, Cairn, Observation – you name it, we climbed it, enjoying the mountaintop experience each time. And now, after more than a decade of climbing up metaphorical mountains in the other parts of our lives, we reconnected back in Alaska to take on another one together. In two days we would participate in the Susitna 100 – not a literal mountain, but a climb nonetheless. The Susitna 100 is a 100 mile loop through the Alaskan wilderness, which winds its way through the woods, across frozen lakes, and along the ice-covered Susitna River. Part of the route follows the Iditarod trail on which the famed sled-dog race takes place each year. Alongside about a hundred others, we would ride our fatbikes, fully loaded with survival gear, through the Alaskan winter.

It was good to see Matt again. And it didn’t take long for the familiar excitement of an adventure together to make that decade apart feel like nothing. We knew each other the way only childhood friends could, having shared countless formative experiences. It’s a rare and valuable thing to be known that way. We caught up over Alaskan Amber and pizza at the Moose’s Tooth in Anchorage. Conversation flowed effortlessly from work and family joys and concerns to goofy banter about cycling gear and the unfamiliar challenges of riding in the snow. It was good to have a companion on this crazy adventure.

And it really was a crazy adventure. Throughout my bikepacking career I had often come across tales of cyclists participating in Alaska rides like the Susitna 100, and I had considered these events to be the ultimate challenge both mentally and physically, the pinnacle ride being the Iditarod Trail Invitational, a 1000 mile journey along the entire Iditarod route from Anchorage to Nome. Rides like JayP’s Fat Pursuit, the Arrowhead 135, and the Susitna 100 are qualifiers for the ITI. One had to finish three such events to be invited to participate in the ITI 350 – covering the Iditarod route from Anchorage to McGrath – which, after successful completion, would allow one to return for the full 1000 mile event.

So, back in the summer of 2017 I decided to sign up for the Susitna 100 – I had to see if this winter fatbiking thing lived up to its wild reputation. I cajoled Matt in to joining me and we began to assemble all of the necessary equipment and plot out our training schedules, him on the snow covered trails of eastern British Columbia and me on the dirt roads Arkansas. Caught up in the excitement of it all, I got a wild hair and emailed the ITI organizer to see about getting into the 350 based on my existing riding credentials. The ITI was just a week after the Susitna 100 and since I would already be in Alaska for that event why not stick around and go for the big one? To my surprise and delight she accepted my application but gave me a spot on the wait list since the roster had already filled. I would learn if I would move to the active roster sometime after the new year. Either way, I was headed to Alaska, and I was thrilled.

Alaska and Arkansas both hold the title “home” for me. My family is originally from Arkansas. I was born in Hot Springs, went to college in Conway, and have traveled the state extensively over the past decade as priest serving the Episcopal Church. My love for cycling was also born here and has been deeply formed by the Ouachita mountains and the friends who have ridden through them with me. Alaska, though, like my friend Matt, seems to know me uniquely. The people there saw me through all the successes and failures of my youth and claimed me after returning from my journey down the Appalachian Trail while I fumbled through life’s next steps. Alaska has known me as me. So, taking my bicycle up to the Last Frontier meant more than simply entering another race. It would be a homecoming of sorts, and a melding of two great loves. I was beyond excited to make the introduction: cycling and Alaska – fatbike and snow. How would the two get along?

As the big date approached – just two weeks out from the Susitna 100 and three from the ITI – an email from the ITI organizer landed in my inbox inviting me to fill a vacated spot on the roster. The timing was a little tight, but how could I say no? I asked Kate to join me for lunch at our local noodle bar so I could share the news. And over some pan fried dumplings, she gave me her blessing. She and the kids would get into their routine, she assured me. They had done it before, following my SPOT tracker dot online each day – digitally connecting through the miracle of GPS satellites. From past experience, I knew I would miss them more than I could feel at that moment. I changed my plane tickets, sent off my registration fee, and started to mentally prepare. The Susitna 100 was just a century, right? I had done lots of centuries before. It would be a perfect warmup for the more challenging ITI a week later. I had this.

The day before the race Matt and I took our fully-loaded bikes on a test ride on a trail just outside of Anchorage. We had a stellar view of Denali in the distance and of a moose just 50 yards away. My bike and Alaska seemed to be getting along just fine.

The Susitna 100 started at Happy Trails Kennel, the home base of four-time Iditarod sled-dog race champion, Martin Buser. Martin has been a dedicated supporter of the Susitna 100 over the years, and an inspiration to all of the riders, runners, and skiers bold enough to roll up to the starting line. As Matt and I drove up in the wee hours of race day, the dogs were up and yelping, as if to welcome the intrepid cyclists onto their historic trail. Like any other race I had been to, the parking lot was full of nervous racers, absorbed in their thoughts, pumping up tires and making sure all the necessary gear was accounted for – the only difference was that the temperature was -8 degrees Fahrenheit. I made the mistake of touching my steel fork with a bare hand while strapping on a bag and felt an instant burn. This was surreal. After a last minute hot water top-up for my water bottles, Matt and I rolled into the crowd at the starting line and the gun went off.

As I would come to learn, the extreme temperatures are a major factor on these rides. That sounds like a obvious statement, I know, but the idea of -8 degrees and the reality of -8 degrees are vastly different. The disconnect is akin to packing food for a bikepacking trip on a full stomach – you tend to underestimate how hungry you think you’ll be out there and you often pack less than you need to. For me, the unanticipated reality of riding in the cold was that it is inescapable. When you are riding you can’t wear your heaviest clothing or you will sweat too much, and if you stop for awhile you will get cold – unless you take the time to put on your heavy coat – but then you’re not moving, which means you will spend more time out in the cold! The trick to keeping hypothermia at bay is to find equilibrium among pace, layering, and temperature. And at around mile five I feel like I had gotten a feel for it, save for the fact that my pace seemed significantly slower than that of the other racers.

Matt and I had a talked about allowing each other the freedom to go at our desired paces – everyone’s equilibrium is a little different – and he shot out at the start fairly quickly. I took it easy in order to get my bearings, as I tend to do at race starts. After an hour or so, though, I just felt sluggish. My “always go pace” wasn’t as quick as it should be, and I could no longer see any other riders behind me (“Always go pace,” by the way, is the pace at which I feel I can maintain, or “always go” regardless of how long I’m peddling. It tends to correlate more with heart rate zone than actual speed, I think. I know it when I’m in it.). And so, just five miles into the Susitna 100 the self-talk began. I thought I would at least have gotten a few more miles behind me before I had to start reciting internal mantras: Ride your own ride. One pedal stroke at a time. Keep on truckin’. These magic little phrases wouldn’t make me go any faster but they would, hopefully, keep my head in the game. And then out of nowhere I got passed … by a runner dragging his sled full of survival gear! I couldn’t quite believe it. What was going on? I hadn’t stopped anywhere. Was I really just this slow? Had all those hard miles I had put in back at Lake Sylvia in Arkansas really earned me no more than the back of the pack up here in Alaska? It just didn’t add up.

The next 20 miles were rough to say the least. The mantras weren’t quite cutting it, although I did manage to pass a few riders, which gave me a boost. A couple poor guys were trying to troubleshoot mechanical issues and another couple were struggling to haul their bikes up a steep icy slope – I wasn’t the only one fighting the fight. I played a game of leapfrog with my runner friend for awhile, which was a pleasant, but incredibly humbling diversion. That guy was a beast. He got to know me by my bib number and we would encourage each other whenever one of us passed (I scored the memorable bib #1 by virtue of having Alexander as a last name.). But I just couldn’t manage to shake this heavy feeling of dread. I wasn’t necessarily having “fun” per se and calculating a finish time based on my current speed was just depressing. The painful truth I could no longer keep out of my mind was that the ITI was simply out of reach for me. I’ve always been wary of making big decisions during difficult moments, but somehow this was different. It was more fear than exhaustion, I think, more of a growing understanding that failure out here had real consequences. I just didn’t want to get in over my head, and realizing that the ITI was over my head hit me pretty hard – a crippling blow to the ego.

At one overwhelming moment around mile 25 the weight of it all just took me down. I stopped right in the middle of the trail, bowed my head over my handlebars, and cried like I hadn’t cried in a long time. Would my tears freeze too? I had dreamed about the ITI for years and had been planning for months. I had been granted a spot on the roster, the event was just one week away, and the drop bags I had prepared were probably already on their way up to the Finger Lake and Rohn checkpoints. The ITI was to be my “next thing,” the event I had graduated to after having completed the Tour Divide – I was supposed to do it. And yet, winter fatbiking was slower, colder, and more mentally exhausting than I could have imagined. I couldn’t fathom setting up a bivouac in these temperatures, dealing with frozen gear and food, and giving it my all just to barely maintain a four mile per hour pace. This was not how this was supposed to go.

The outburst surprised me, but I found myself grateful for it – my body taking control for a moment to let my mind know that it needed to slow down and begin to triage my thoughts. I looked up. The sun was out, the sky was bright blue, the landscape was breathtaking. The storm was in my mind. I realized that I had to let go of the ITI and concentrate on the Susitna 100. I was just a quarter of the way through my current ride, and if I didn’t put my attention where it needed to be, right here and now, I risked the possibility of losing both rides. Every thought about the ITI was draining precious mental energy away from my current predicament, and I didn’t have an ounce to spare. I had to let it all go – not just the ITI but also frustration with being at the back of the pack, depression about pace calculations, and the ego slap of being passed by that machine of a runner! I had to be here now. And so that became my new mantra: Be here now. Be here now. Be here now.

I began again.

The next 40 miles were much better. The terrain didn’t change – in fact, the snow softened up a bit around midday and I was forced to get off and push for a few miles. The temperature didn’t change all that much either. It was still cold. And I can’t say that I ever really picked up the pace. The change, though, was in my head. The raging storm inside calmed down enough for me to began to see things a little more clearly. In fact, I got a cathartic laugh in at one point!

It turns out that crashing is a fairly common occurrence while winter fatbiking. “Crashing” may actually be too strong of a word to describe the phenomenon. It’s really more like gently falling into a soft, cold pillow. I know from experience. Occasionally you’ll run over an unexpected soft spot and lose your balance, or you’ll drift too far to the side of the trail, get sucked into the berm, and ignominiously bite it. It’s never graceful! Although I was alone for much of the ride, I felt the presence of kindred sprits throughout – often witnessing large indentations in the snow on either side of the trail unmistakably marking a fall. At one point I saw a fellow biker get pulled into a berm. I heard an explicative and then, seemingly in slow motion, the rider just disappeared down into the side of the trail. I rode up and complemented her on her “perfect 10,” and asked if she needed a hand. With a resigned look on her snow covered face she replied, “save yourself, man … save yourself.”

Despite the challenge, I think a ride like this can tap into the child in us all. We try to avoid crashing, of course, but when we do inevitably have to dig our way out of a drift, it’s an instinctive reminder of the joy to be found in playing in the snow. I came to think of those indentations on the side of the trail as snow angels.

Another boost to the spirit this next section of trail provided was the opportunity to enjoy the awesome hospitality at the checkpoints. In particular, the folks at Flathorn Lake (mile 32) and 5 Star Tent (mile 46) were God-sends. A little warm stew and diverting conversation can do wonders for a beleaguered rider. The Flathorn crew had decorated their hut like a Hawaiian Luau complete with straw skirts and coconut bikini tops for the volunteers – worn over Carharts, of course. One of the volunteers was actually a friend of a friend and so we had some fun talking about our mutual acquaintance. To be honest, I can’t really remember many details about the conversation given my compromised, but improving, mental state. I was just grateful to have someone to keep me company while my glycogen stores recovered.

The folks at 5 Star Tent were equally entertaining. Honestly, the whole experience there was a little bizarre. A ski plane crash landed near the tent earlier in the day and a snowmobiler recently came through looking for emergency services having broken her arm in an accident. Thankfully neither the pilot nor the snowmobiler had life-threatening injuries, but the unexpected activity of it all seemed to scatter the volunteers. There was a good deal of fuss over how to get the crock pot to heat up, if I recall, and someone else was struggling to blow up balloons. And all this was taking place right in the middle of the foggy, frozen Susitna River at dusk. It struck me again just how unique this journey was. The world outside was unquestionably bleak and yet these hearty volunteers were warm and joyous – sort of an Alaskan hallmark, I think. The only way to escape the persistent bite of the weather was to discover the delight in human relationships. And during my brief visits at the at the checkpoints in the middle of nowhere, these Alaskans graciously shared their secret with me.

Night fell, so did the temperature, and as the hours progressed all became quiet on the Susitna. The snowmobilers out preparing for the Iron Dog Race turned in and left the human-powered adventurers to carry on. Three or four other cyclists and I matched pace for awhile, following each other’s blinking tail lights, shouting encouragement here and there, and offering temperature readings and mileage stats as we pushed our way to the next checkpoint. The buzz on the trail was that EagleQuest Lodge was a little haven. It actually had a grill that stayed open all night, welcoming tired, hungry cyclists – and tempting them to throw in the towel. Given the slow pace, it seemed to take forever to go the 20 miles from 5 Star Tent, but I eventually rolled up to the lodge just after Midnight. There was a large group of people congregated at the turnoff, and I assumed they were the welcoming committee – but I didn’t get much of a welcome. I found out later that they were a news crew awaiting the arrival of the first runner, who was reportedly not all that far behind. That runner AGAIN! Was I ever going to shake that guy? He was like this constant check to my ego, continually taunting me. Ride your own ride. Ride your own ride.

EagleQuest Lodge was all I could have hoped for and more. There was a bonfire outside surrounded by volunteers who helped me off my bike and oriented me to the cushy amenities the place had to offer. There was, indeed, an open grill inside, a drying rack for wet gear, and several cabins available to take a nap in – which sounded risky. There were also a lot of bikes around. I had finally caught up to some of the pack!

I dragged myself into the lodge, hung up my gear, and sat down with some tired, ragged looking riders (I’m sure I fit right in), and ordered a breakfast sandwich and hot chocolate. A little protein, a little sugar, and I’d be good to go … or not. Just a few bites and my stomach began to protest! One of the keys to successfully getting through an endurance event is having a well-developed “junk gut.” The more calories you can shove in without having it all come back up the better. Apparently my junk gut wasn’t quite as honed as I had hoped and this sandwich was doing me wrong. I let it sit on the plate as I assessed just how severe my reaction was going to be. I must have sat there for quite awhile because I remember being jerked back to awareness when someone from across the room asked me if I needed help finding some motivation to finish my sandwich. I smiled sheepishly then decided to cut my losses with the lodge and get moving. As soon as I got up I knew something was wrong.

My vision started to darken and my ears began to ring – I was going to pass out. I stumbled through the dining room, trying to stay conscious, and somehow made it into the restroom. Looking into the mirror, my face was completely white and a cold sweat had broken out on my forehead. I splashed some water on my face and took a few deep breaths, trying to calm down. The last time I had passed out was during a blood drive in college; struggling to maintain consciousness is not normally something I have to worry about. This ride was proving to me, yet again, just how much I had underestimated it. Fortunately, after a long conversation with myself in the mirror, I regained my composure and decided to find a comfortable spot to rest my head while the nausea passed – there was no way I could go back out there in my current state. I had heard there was a quiet room with a heated floor nearby. Sounded perfect.

As I entered the room I was met with quite a sight – about a dozen or so other riders sprawled out on the floor sound asleep. Apparently I wasn’t the only one in need of a reboot. I found a spare couple of feet on the floor, wedged myself in, and had a few blissful moments soaking up the heat radiating from below. I allowed myself some time to drift in and out of sleep, unsure as to how I was going to eventually pull myself away from the Siren song of EagleQuest and journey back into the frozen night. Yeah, Matt was out there somewhere, and if he had to wait for me at the finish line, well, he could deal. I needed a minute.

Eventually I got up. I don’t know how, but I managed to shake the fainting spell and nausea. As much as I loved that heated floor, I needed to put that sandwich and the misery it caused as far behind me as I could. I refilled my water bottles with hot water from the restroom tap, crawled back onto my bike and got a hearty send-off from the volunteers outside around the fire. EagleQuest was at mile 63 which meant I had 37 miles to go and two checkpoints along the way – one at mile 80 and the second at mile 90. I could do this.

It felt surprisingly good to leave EagleQuest behind. The break was much needed (the sandwich, not so much) but my journey was not complete. In the spirit of promoting good morale by celebrating every little victory, I congratulated myself for resisting the pull of an early finish line. But once again I was out in the cold, forced to move forward or freeze.

The trail took on an eerie feel in these early morning hours, weaving its way between open lakes and dense forest. An icy fog formed over areas near the lake shores, obscuring the way ahead. I was forced to keep my eyes on the few feet just ahead of me, looking for tire tracks and trail markers. Riders do take wrong turns out here. In fact, back at EagleQuest there was talk of a couple who managed to go ten miles in the wrong direction – that’s a solid two hours of riding – and then have to double back. There is nothing more discouraging to an exhausted rider than realizing they have been putting in unnecessary miles. Fortunately, I had managed to keep to the right path so far, but my new challenge was holding my eyes open so I would stay on it. I have never been a fan of rides that encourage sleep deprivation, and adding a three hour time change from Arkansas to Alaska compounded the issue somewhat, I think. Repetitive pedaling over an absolutely flat lake can have a sedating effect. At one point I had to get off my bike and jump up and down in order to wake up.

At this point in the ride, the finish line couldn’t come quickly enough. I had seen the Alaskan wilderness in all its glory, and it had put me in my place. The Susitna 100 had humbled me many times over. It was time to simply get this thing done. Other than warm broth and inviting smiles, The Cow Lake (mile 80) and Big Hunter (mile 90) checkpoints seem to blur a bit in my memory, but I will never forget the last ten miles.

Not long after leaving Big Hunter for my final push I came upon none other than the runner. With a strand of blinking, multicolor Christmas lights running down the tether to his sled, he was hard to miss. Unlike our time together during the first part of the race, there was no playful banter. Instead, just a wave and a “good job.” I could tell the distance was wearing on him. And why not, after virtually four consecutive marathons … in freezing Alaska? After the race I learned that “the runner” was none other than David Johnston, the record-holder for the ITI 350 foot race category. His exploits are legendary. It was an honor to share same trail for a time. I did pass him, though. There was no way this guy was going to beat me!

As I rode the final few miles of the loop back to Happy Trails Kennel, it struck me just how much of an emotional journey this had been. Sure, riding 100 miles through the bitter cold was a respectable physical feat, but I don’t believe I had ever crammed so much mental processing into one 24-hour period. My brain actually felt more exhausted than my body. What started as a mere prelude to a larger event became the event in itself, and that change was painful and all-consuming. I often find myself preaching about the value to be found in enjoying the present moment, indeed, this blog is based on a Shunryu Suzuki quote to that effect. Learning to live in the now can bring a certain peace and perspective that cannot be found while fixating on the future. Never, though, had I been through an experience that so clearly drove home the point. Were I to have remained focused on the ITI, I’m not sure that I would have been able to make it through the Susitna 100. Choosing to “be here now” is not merely a choice about whether or not to be happy in life – it is a choice about whether or not to actually live. If you’re not careful, the hypotheticals of the future can get in the way of what is truly in front of you, stoping you dead. The ITI could wait. I had a race to finish.

Matt was waiting for me as I rolled into Happy Trails – over 22 hours after leaving it. I’ll never forget the look on his face. He said “congratulations,” but the nonverbal subtext was, “Jeez man, you were out there a long time. Sure you’re okay?” I asked him how long he had been waiting and he replied under his breath, “a while.” It turns out he had been there for six hours. The man is a beast! I parked my bike, shuffled into the Kennel, grabbed some cold nachos and a warm Coke, and none other than Marin Buser, the Iditarod champion himself, walked up to congratulate me. And, you know, I felt like I deserved it.

As Matt and I packed up and prepared to go our separate ways, we talked about plans for our next mountain climb. Matt suggested, and I think brilliantly, that we use John Muir’s Travels in Alaska to plot a course up Glenora Peak in British Columbia, retracing Muir’s steps during his adventure in the 1880’s. Apparently Muir took a minister along with him on the journey. Unfortunately, though, that minister ended up dislocating both of his arms during the climb, foiling Muir’s plans to reach the summit. We decided that our bid would be more a redemption story rather than a reenactment – and we decided we wouldn’t let another ten years pass before we made good on the plan!

There is a final twist to this story – sort of a cosmic joke of which I am, unfortunately, the butt. As I disassembled my bike I realized that in my anxious pre-ride fog I had managed to mis-thread my chain through my rear derailleur, causing it to rub significantly. In fact, I discovered that the part of the derailleur the chain had been rubbing on for the entire 100 miles was almost sawed through. All you bike people out there reading this … just think about that for a minute. Yeah, I unnecessarily added God-only-knows how much extra resistance to my ride. I guess the constant sound of the tires on the snow and the heavy load on my bike kept me from realizing the mechanical ball and chain I was unwittingly dragging along. Alas, I will not blame the difficulty of the ride on my error – but I would like to take on that runner again!